While I used the most inflammatory framing I could for the title, the answer is, of course: neither. They’re a tool and the trick is how and when to use them effectively?

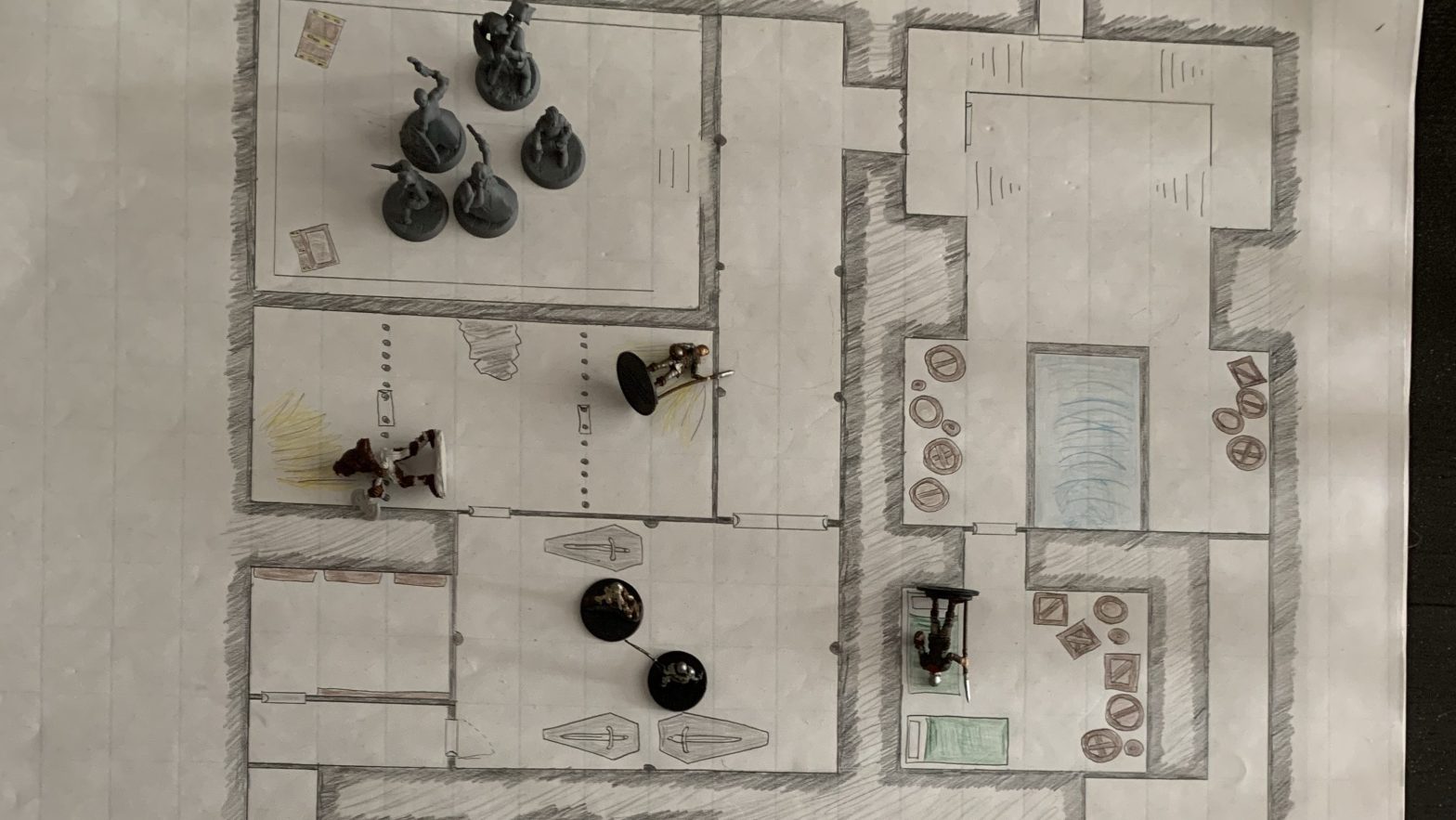

Spoilers for Critical Role, vague for most of it but I don’t want to figure out which episodes so say all of C1 and C2 up to E127, and the Lost Mine of Phandelver adventure. And minor spoilers for a campaign I’m running so if any of my players read this, it shouldn’t be too bad, but you will know I made some maps, for… some reason, who can say? Also you’ll get to see some self-critique.

Battle maps, and by extension “tactical” combat encounters, are a pretty divisive and evolving subject. In an interview with Sly Flourish, Crawford dropped that “None of the Wizards design team uses miniatures anymore. Chris Perkins got rid of his huge vat of miniatures…” preferring to use more abstract or Theater-of-the-Mind styles of combat. Actual play podcasts thrive and generally use TotM for their audio format. And yet there are thriving communities of battle map artists and patrons. Dwarven Forge has raised something like $20 million dollars on Kickstarter from supporters eager to have not just maps, but terrain (which, I mean, it’s so tempting).

I have been thinking about maps lately because the campaign I’m running has struggled with pacing and maps have—I think—been big contributors to that. We started with Phandelver, even though it’s diverged more and more, I used the published maps to start. Pre-pandemic, I’d actually copied some of them to 1-inch grid paper. More recently I just uploaded the images into Roll20 and tweaked the sizing until the grid pretty much fit.

I have criticisms of Phandelver to save for another post, but for a new 5e GM, it was definitely helpful for a time. But here I’m going to talk about the maps.

A lot of the maps in the adventure are designed around the idea of a series of small encounters. When you sneak through the Cragmaw or Redbrand Hideouts, or infiltrate Cragmaw Castle—which you can do without starting a fight if you try—or explore Thundertree, which is really an outdoor dungeon crawl. There are opportunities to take breaks, even short rests can be viable. And the first two more or less worked that way. We put out the map, we’d move through it, occasionally a quick fight would break out, and then it would finish.

But with the next two, something different happened: all the encounters ended up strung together into giant, lengthy (as in whole-session-and-then-some, one was 16 rounds—I’ve never seen someone need to recast Spiritual Weapon before) combats. The PCs split themselves up, ran into new rooms during the fight, made noise and didn’t stop enemies from shouting for help. Multiple sessions had to end at the top of a combat round, something I really try to avoid.

The maps had worked well as tools for exploration, but now that was devolving, and detracting from non-combat solutions.

There are a few other variables that are worth pointing out:

- This party is relatively large at 6 PCs. I think this matters.

- The first two maps—Cragmaw and Redbrand Hideouts—were in person, on paper.

- The second two—Thundertree and Cragmaw Castle—were online on Roll20.

Over the holidays I ran a one-shot for fellow DMs Noam and James. We wanted to try out Tasha’s Sidekicks, so there were effectively 4 PCs, but two were simpler. I also challenged myself: don’t rely on maps. It was a nice way to practice theater of the mind, and the combats were fast—we got through three in a relatively quick session, with some puzzles and non-combat encounters thrown in, too. They were also simple, the enemies weren’t intelligent or tactical.

A recent session in which I’m a player involved an encounter—it didn’t start, or have to end, as a “combat” encounter—in a densely urban environment. Noam, the DM, had tried to create maps for it but struggled with scale. 5-foot grids covering a chunk of a city get large quickly. Instead we used a city-scale map more abstractly, not representing literal distances or even entirely literal buildings, just for a sense of relative locations. Noam had been worried about his perceived lack of prep going into this—ostensibly an “easy” moment to prep for since we’d left the previous session on a cliff-hanger and he knew exactly where we’d be and what was happening—but the players all said it had worked really well. It was a bad fight (my character is a retired Assassin Rogue, he does not like fair, face-to-face fights anyway). We ended up fleeing, which is rare enough by itself.

In a group chat of fellow DMs, we started digging into this. Did the lack of a map help? Did the presence of even the abstract map subtly nudge some players toward combat solutions? Did having the full city enable things like PCs running down and circling a block?

So, maps! Uh! What are they good for?

One thing maps, especially grid-scale battle maps, have is a strong association with tactical combat. If a map comes out, that communicates to players that the DM had at least planned for the possibility of a fight here, and seems to prime players to look for combat solutions. Sure, they can be tools to aid exploration, but if you’re not in initiative order, measuring time in rounds, the utility of a grid drops dramatically.

Maps also set the parameters of an encounter in a very real way.

In CR Campaign 1, there is a fight in the City of Brass. Matt built a beautiful piece of a city block out of terrain pieces. It was dense, there were all manner of buildings to break line-of-sight or provide cover, street details and detritus. And no one in the party (except maybe Liam/Vax?) considered leaving that area and going “down the block”. They didn’t even consider going to the far side of buildings that they couldn’t see well until Matt had an NPC fly there. What they saw was what there was, and it did appear to have a constraining effect on their imagination.

Conversely, in my campaign, the presence of doors to other rooms opened the encounter beyond what I’d expected. Because it was there, they could go there, and they did. Now I have more things to add to initiative order and 6 encounters become one mega-combat.

(I absolutely believe I have plenty to learn about setting the scene and tone as a DM, and that this is collaborative and I can’t guarantee a certain path or outcome, but I want to set myself up for success, too.)

The flip side of setting the parameters is that maps can enable more complex combat encounters. If the terrain itself is a meaningful part of the encounter, or if enemies or players are going to make use of the terrain and detailed positioning—think of the Oban fight in CR C2—the map can help ensure everyone is on the same page, and avoid “oh I thought… well then I wouldn’t do that.”

And of course, maps take work to create. A disproportionate amount of prep time can go into map creation, especially if you, like me and Noam, aren’t a fan of the more randomly generated style and like to think about the space as real and designed by in-universe actors. Tools like Dungeon Scrawl and Inkarnate can help a lot, especially for those of us who are more artistically challenged, but they can also become time sinks of tweaking.

And, at least sometimes, maps can be fun to make. There’s a reason I built a pretty detailed but useless overland map for a one-shot that was only going to see a tiny part of it.

One thing I’ve noticed on CR is that early on, Matt was more likely to use maps for exploration (like the Emberhold during the Kraghammer arc) but he’s been doing that less. I wonder if some of this is that, as he’s shifted into Dwarven Forge maps, it’s just not worth it. Matt is also incredible at description. He talked the party through navigating the ruins of Aeor, weaving both a clear and detailed sense of physical space with a strong sense of mood and aesthetic.

Matt hasn’t entirely stopped using maps for exploration. In C2E127, the party splits into 2.5 groups, with three characters navigating a basement complex, built out with terrain tiles. Several small combat encounters ensue, with a few different initiative rolls. Each encounter has a chance to end and drop out of initiative, moving back into exploration mode and less rigid time.

There are a few things that I think contributed to this working so well:

- The party was small, there wasn’t much crowding, and they couldn’t rely on anyone else to handle any given situation.

- Matt does a great job of scene-setting, going back several hours into the episode to set this up as an environment where a “quick-and-quiet” approach will probably be best.

- Even when they were not initiative, and freer with time, the time-scales were still close to rounds.

- It was a confined space.

So what’s the “so what” of all this?

I’m going to be thinking very deliberately about how and when I use battle maps.

When the encounter I’m trying to build is something I do expect or intend to result in combat, particularly if the terrain has features that can help or hinder either side, I’ll make maps. After all, tactical combat is a part of the game that I enjoy—but only one of many parts.

The maps I have been making have been simpler. Rather than building whole buildings or environments, I’ve been making a room here, a cavern there. I’ve also been trying to build up a library of pre-built generic maps—grasslands, a forest, a swamp, rocky terrain, etc. The digital equivalent of a grid over a themed background that I can throw some terrain elements like trees or walls onto quickly to make it unique. This covers encounters where, if combat breaks out, having the map can be fun or helpful, but it’s not something I want to spend a ton of prep time on or an especially unique location.

I probably will avoid using maps for exploration, at least not finely detailed, combat-scale maps. Description is a skill I want to improve, anyway, and running exploration without a map will make me practice. It also means exploration can be more expansive, more flexible—this might mean both me changing things on the fly for pacing, or shifting a modular part around, or leaving some blank space for the players’ imaginations—and not prime players that “this is a combat encounter”.

The “maps” I’ve been making for exploration have been graphs: nodes and connections. (Edges and vertices—I am a mathematician at heart.) Location A connects to location B via route 1. Each edge and vertex has some descriptive notes for myself, about the space and any encounters or other occupants. [Edit: there’s good material out there if you search for “pointcrawl“.]

I am going to try to teach myself to not bring out maps too early. Unless the PCs are trying to set up an ambush or have a similar need of terrain to accomplish something, I’ll try to wait until “roll initiative.”

And I’m going to try to purposefully use theater of the mind for combat more often, even for combat encounters that I’m preparing.

I like tactical combat, it’s a facet of the game I enjoy in the right doses. But 6 hours of it can get… draining—especially when it’s not planned, not phased, not climactic—and I also enjoy exploration, role-playing, and creative solutions to challenges. Maps are a tool, and like any tool can be used effectively or ineffectively. My goal is to be more deliberate and intentional about when the maps come out—and about what time goes into them.