Part of a series, maybe? In which I reverse-engineer what I’m sure are basics of game design.

A friend of mine recently picked up Blades in the Dark and we are eager to get into some heisty hi-jinks. Heists are hot right now. I just listened to A County Affair from Worlds Beyond Number, which Erika Ishii ran using a heist-modified version of Roll for Shoes. (So there were, you know, two rules.) I even put together a little mini-campaign pitch, inspired by Tiny Heist.

So, incidentally, I’ve been looking at a lot of different systems and thinking about genre, and how those interact.

Heist stories are pure genre, and the major elements are pretty easy to represent in most TTRPG systems. A group of highly skilled individuals with complementary specialties comes together to accomplish a goal contested by a more powerful force. Stakes are high, and ultimately it’s going to come down to out planning and outwitting, with some parts of the plan kept hidden.

Representing Skill

Skill isn’t unique to the heist genre. Robin Hood was an uncanny archer. Anakin Skywalker was a talented pilot. Baby isn’t just a good driver, he’s the best.

When we use dice in TTRPGs to inform the story, we want to adjust the odds to support the fiction. The Rogue should be “better” at picking locks than the other characters, so even though there are dice rolls involved, the Rogue should succeed at that skill more often than other characters would. The Ranger should be able to split the arrow when they want, or at least to have a solid chance, while it would be an amazing random event for everyone else. Like a heist, we want the characters to have unique roles in the story—and we like them to have flaws and weaknesses—so we want to create some kind of skill differential.

d20 systems, like D&D and Pathfinder, and Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA) use a modifier as the primary mechanism for representing skill. We roll some set of dice and then add to the total. That total is how well a particular attempt went. Each character’s set of modifiers, whether it’s Strength and Intelligence, Charm and Weird, sets them apart. A character with a high modifier may be able to achieve things that other characters simply can’t, no matter how lucky. (“That’s a… 41 for Stealth.”)

Blades in the Dark (BitD), Roll for Shoes (RfS), and World of Darkness (WoD; like Vampire: the Masquerade [VtM]) use dice pools. MI-6’s Q would roll more dice for Tinkering than Bond. Since “plus modifier” isn’t a consistent requirement, there’s more flexibility in how success is determined: BitD uses the highest die rolled; RfS sums up the dice; WoD counts the number of successful dice. Each of those methods produces a different distribution of successes—and requires a different way of representing “difficulty”—but fundamentally a “higher skill” means “more dice.”

Kids on Bikes uses a modifier and the size of the die to represent skill. Evan Kelmp rolls a d4 for Charm, while Sam Black rolls a d20. Since the dice explode, it is possible for Evan to hit a 10 Charm roll, but not likely. For Sam, it’s expected.

Representing Difficulty and Interpreting the Results

There are a few ways systems represent the difficulty and result of a task. d20, RfS, KoB, and WoD require some number to meet or exceed a target set by the GM based on the attempt to succeed, otherwise the character fails. PbtA and BitD use absolute thresholds, where the targets are set ahead of time. The absolute scales allow PbtA and BitD to build in the idea of “mixed success” in a more natural way, but in exchange GMs have limited options to adjust the difficulty of a particular task.

There’s nuance within the “GM sets a target” systems. Among d20 systems, Pathfinder and older D&D editions use something of a sliding scale to adjust the odds to what the DM thinks is appropriate. In D&D 5e and KoB, there is an absolute scale of task difficulty independent of skill. In 5e, a DC 20 skill check is anything that is “hard” to accomplish, not necessarily hard for this character—i.e. a level 11 Rogue may succeed automatically at some hard tasks. In KoB, a 20 is “a task at which only the most incredible could even possibly succeed.”

(Warning: Math) Adjusting the Distribution of Results

How you represent skill and how you determine difficulty and results is one mechanical question. Another is how you want to distribute those results. How much of a different do you want skill to make? Is there a certain type of result you’d like to emphasize, like failure for a “universe is against us” feeling, or mixed for a “actions have consequences” vibe?

(All of the graphs here are from the wonderful AnyDice tool.)

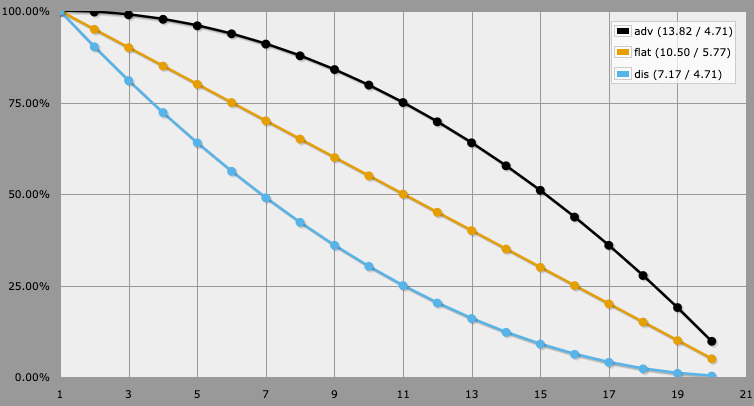

Rolling a d20 has an equal chance of hitting any side. If you need to hit an 11 or higher (with no modifier) that’s 50%. Adding a modifier adjusts the minimum, maximum, and average of the roll, so over time a Wizard with +7 to Arcana should average 17.5 to Arcana checks, instead of 10.5. The probability distribution function for hitting “at least X” has the same shape, shifted left or right.

(Technically this is a graph of P(1d20+m ≥ X), not exactly the probability distribution function [PDF]. But the PDF is hard to see because it’s three overlapping flat lines at 5%.)

So, in d20 systems except 5e we should see that Wizard hit DC 15 Arcana checks more than half the time and DC 20 less than half the time. In 5e, we have advantage and disadvantage which actually do change the distribution of results:

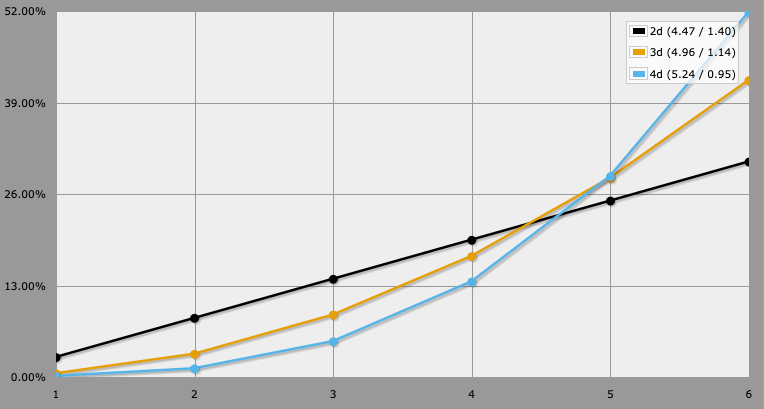

In PbtA, we roll 2d6 plus a modifier. That produces a different distribution (this time as an actual PDF):

And P(2d6 ≥ X) for comparison with the d20 graphs:

This choice pulls the bulk of rolls over time in toward the center—which, in PbtA, means, with modifiers, more rolls will end up landing in and around “mixed success” than full success or failure. PbtA is good at “yes, with a but” storytelling. You can accomplish this, but it will cost you.

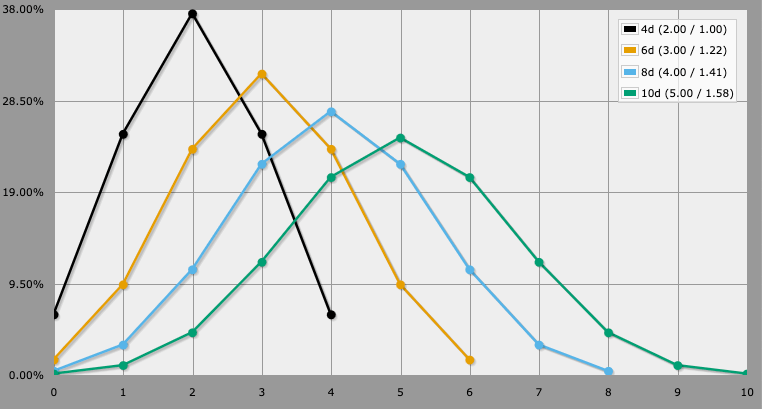

BitD’s “pick the highest of N dice” makes for a very different family of distributions. Combined with using small d6s, skill rapidly increases the odds of getting a great outcome (rolling a 6) and makes a fully bad outcome (rolling a 1–3) increasingly unlikely. (Shown here as PDFs.)

Picking d6s makes great outcomes more likely. If we to adjust the BitD results scale along with the die size, e.g. max is a full success, top half is partial, bottom half is a bad outcome, a few trends appear. The odds of a bad outcome are the same—for 3d, it’s exactly 12.5%, which is the same as flipping 3 coins (3d2) and getting all heads—but the odds of a full success get smaller. For 3d6, the there’s a 42% chance of rolling at least one 6; for 3d8, it’s only a 33% chance of at least one 8; for 3d10, it drops to 27%.

The die size also affects the odds of “critical” successes, e.g. rolling the max number on more than one die. The larger the dice, the rarer the crits.

WoD’s mechanism of “count the number of dice that exceed half” produces interesting results where skill makes it possible to succeed at tasks that are too difficult for others by stretching out range of possible results. Here we see the probability density of different numbers of d10s producing X “over 5” rolls:

The die size doesn’t affect this distribution in the same way that, say, adding multiple dice together does—like BitD, it affects the rate of critical successes, i.e. rolling multiple max-value dice. Using d8s instead of d10s would skew rolls toward PCs exceeding their own expectations.

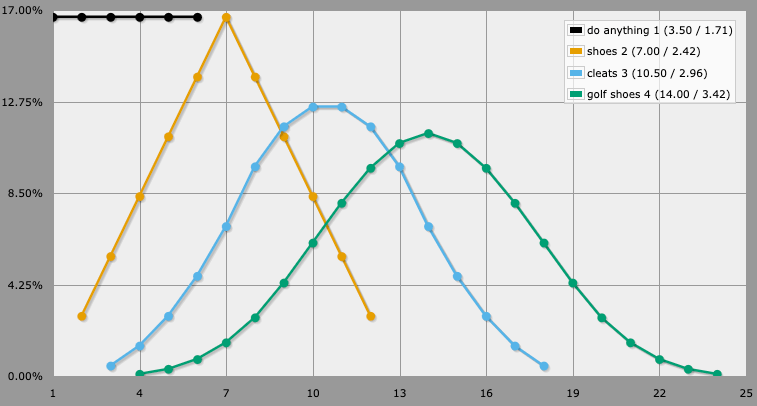

The RfS system of adding multiple dice together combines several of these features. It moves the average, the maximum, and the minimum. Whether in a contested roll or if the GM sets a target, the impact of skill is huge—which is only slightly balanced out by the nicheness of those advanced skills. RfS is truly designed to make things spiral wildly out of control.

So what?

The system of representing skill and success in TTRPGs controls how likely different outcomes are in uncertain situations. We would need to consider other factors like situational adjustments, GM discretion, mechanisms like Inspiration or Heat, etc, to get a full picture. But we can start to see some trends already:

- Using a fixed scale like PbtA or BitD shifts the feeling from “how hard is this thing” to “how well do you do it.” It also makes “partial success” easier to manage because it’s fixed.

- With “how hard is it” systems, partial success requires adjusting a window around the target. For example, Pathfinder 2e frames this as a “fail DC by 10 or more” threshold for critical failures and “exceed by 10 or more” for critical success, giving us four potential outcomes: crit fail, fail but it could have been worse, succeed but it could have been better, crit success.

- If extraordinary success requires hitting the max, bigger dice make extraordinary success less likely, but otherwise they only impact the scale for other numbers, like the outcome thresholds or modifiers. If too much extraordinary success risks making a game too cartoony for the genre, try increasing the die size.

- On the other hand, if you want more of those moments, try decreasing the die size.

- Adding more dice and picking the highest reduces the odds of failure faster than it improves the odds of success. That makes skill more consistent, meaning fewer moments where the Barbarian rolls a 9 (2 + 7) on a Strength check and the Wizard rolls a 18 (19 – 1).

- Summing multiple dice pulls results toward the mean. In a system like PbtA where skill is a modifier and the number of dice are fixed, that can be useful for skewing towards a “mixed” result.

- Adding and summing multiple dice also moves that mean and rapidly expands the range of outcomes. This is great for chaos, and maybe out of place in a more serious world.

- However, the WoD system of counting dice that meet a threshold has similar properties, with less of a tendency towards the mean and slower growth of the max.

I’m not planning to make a game system any time soon, but I thought this was an interesting set of knobs that can affect story tone. And I needed to write it down to get it out of my head so I can do other things today. 😅