Three related things recently:

First, Colville using guns as an example of his rule design process (an interesting topic for another time). He talks about how you want to create mechanics that encourage the fiction to happen.

For example—if you don’t want to watch the video right now—if you’re creating a sub/class around a Western-style gunslinger, two iconic actions are the quick-draw duel and fanning the hammer of your six-shooter. So, can you build in mechanics where, if you take those actions, you’ll feel like you’re in Unforgiven? And if, like many of the commenters on the video, you want to feel like a swashbuckler sailing the Spanish Main with a blunderbuss pistol, what mechanics could you design to make that work?

I also started watching some of Brennan Lee Mulligan’s Adventuring Academy videos, and obviously I had to check out this conversation with Dael Kingsmill which spends quite a lot of time on homebrew:

In it—spoilers—they start talking about how the mechanics of attacks and saving throws feel different. When you, as a spellcaster, cause a creature to make a saving throw, it’s a spell that simply happens. There’s no attack, there’s no missing. There may be a contest of wills and no guarantee that you’ll win, but you’ve already bent reality. An attack, on the other hand, is a practiced, refined action, a demonstration of martial prowess and skill.

Similarly, traps or hazards that require saving throws create a sense of danger that’s happening to you, things that are out of your hands.

Using Skill Challenges

Before I saw these videos—unfortunately, because this probably would have saved me some time—I was working on prepping a session and it was not going well.

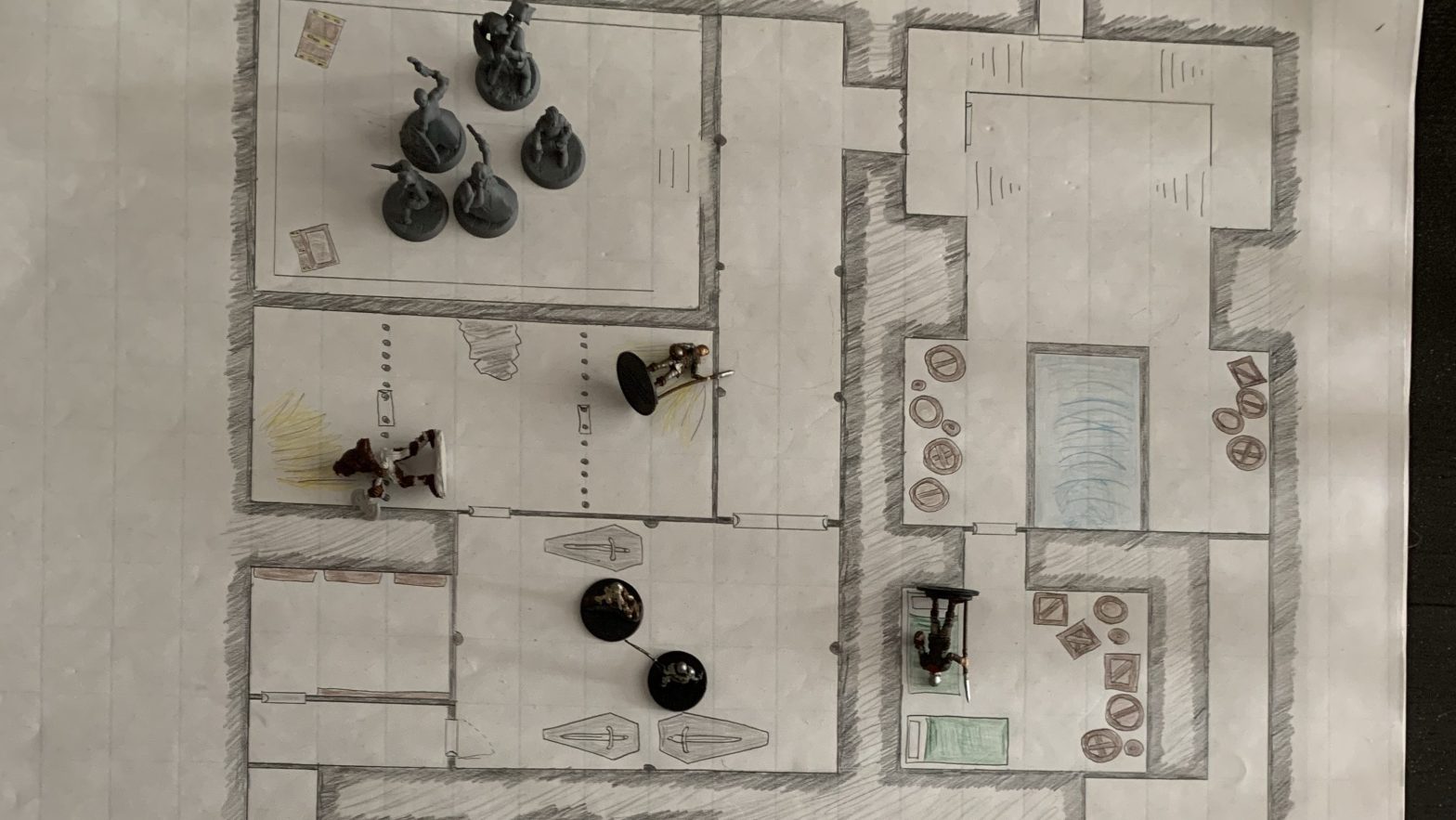

The party has been making their way to a long-buried Dwarven delve, through a path that’s opened because of some geological instability. I had designed a pointcrawl version of a map. I wanted it to feel like a dangerous honeycomb of tunnels, a place with no clear paths, full of various hazards. I had notes about each node, and environmental details on the edges that would foreshadow where they were going.

I hated it.

I wasn’t convinced any of these were great encounters. Even as interconnected as the map was, it didn’t feel like Shelob’s lair, but I felt like if I approached a connected graph, it was going to make too many meaningless choices for the party. Or at least apparently meaningless, since I wasn’t sure how to communicate that they were on the right path until they stumbled onto the end. I wanted the characters to feel lost and frustrated, not the players.

This was leaving me uncertain about whether I wanted to include this part of the journey at all. If I couldn’t make it fun, why have it? They’d already gotten to do some cave exploration and combat. We could skip ahead. Was this worth a whole session?

The breakthrough was: what if it were a half-session skill challenge? Could I abstract away the tangle of intersecting caverns while not relying on them somehow guessing what the real paths? Could I influence the pacing a little more? Could I possibly encourage some more creative problem-solving than “I guess we go right”?

Inspired by the Mighty Nein’s journey to Isharnai’s hut, I took the encounters I had stashed in various corners of the graph—a mix of combat and hazards—and put them into a table. I figured out how I would introduce this, starting with a mediocre-DC Survival check. I figured out how many successes would get them there.

I had landed on a mechanic that I thought would better evoke the sense of the fiction I was going for. Not in those terms, but now that I have those terms, I think it’ll be easier to identify those moments.

And the results?

Of course, it didn’t go perfectly.

The party did come up with some interesting ideas—attempting to find and talk to any animals, using Boots of Speed to quickly investigate several paths, trying to roll a ball-bearing to detect the slope of the cavern.

Unfortunately, they rolled like shit. I think they got a single success against DCs that were in the 10–14 range.

They also spent a goodly long time investigating a mundane rock. They drank water infused with slightly psychedelic mushrooms (I thought I was writing that mechanic just to entertain myself, but I then got to ask “you’re drinking it? the water from the mushroom pool?”). They investigated an alternative path through an underwater tunnel, but rolled poorly on some of those checks as well and didn’t want to take the dive of faith. They used an herbalism book I forgot about—and some ridiculous Nature rolls—to avoid some brown mold.

They triggered a couple of combats that I rolled, which they absolutely destroyed. One of them ended with a floating skull trapped in a chest and now in their possession.

So my half-session plan ended up being the second half of the session. But they failed their way to the end and made it!

There were a number of things I could’ve done better. One thing I think I need to do is simply describe more. I think I worry about taking up airtime or not being an especially captivating storyteller, but it leads me to shortchanging the scene-setting, which probably makes the description I do spend time on even worse. There was one opportunity for an Animal Handling roll, which I wish I’d taken in retrospect, because how often do you get to use Animal Handling?

I want to create more opportunities for creative problem-solving, and ensure I’m rewarding it—or at least giving it legitimate opportunities to work. It’s fun, and with a mix of newer and veteran TTRPG players, practice is always helpful.

Mostly, it was an object lesson in thinking about whether and how mechanics—as much as narration, music, etc—are encouraging the mood/genre/fiction.