A friend asked a question the other day that I’ve been thinking about: why is it that my character rises up as a hero and not, say, the blacksmith whose smithy was burned down by a dragon?

There’s a lot to unpack here, and I think it’s really interesting, but I don’t want to keep blowing up discord. So: blog post!

Spoiler warnings for this one: probably minor but Lost Mine of Phandelver, The Hobbit, Critical Role campaign 1, the Critshow.

The short answer is: maybe the blacksmith will! There are at least three angles here: the historical design and context of D&D specifically; the in-universe question, within the world of the fiction; and the meta narrative concept of the fiction.

I quite enjoyed Matt Colville’s series of videos on the History of D&D. In the first entry, on OD&D/1e, he digs into some of the language Gary Gygax used, and his influences. Notably, Gygax anchored the game in pulp fantasy, sword & sorcery like Conan, and pointedly left out Lord of the Rings, which is more epic fantasy and was wildly popular at the time.

Gygax (paraphrasing Colville here) also thought the rules should generate the world. Early D&D has some baked in assumption that all games take place in the same reality, and that the collective actions of the players should lead to a collective fiction that was the setting. Elves and Dwarves were rare in the fiction, so the game rules were designed to ensure that they would be rare among the player characters.

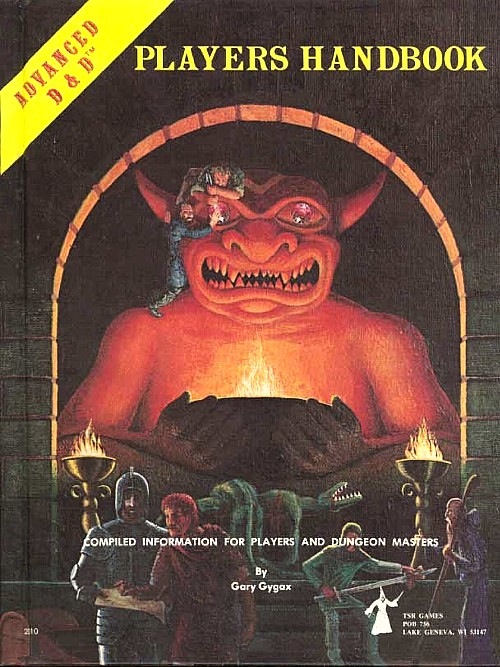

This must also mean that adventurers were fairly common, in the fiction. Sword & sorcery “heroes” aren’t always out to save the world—they’re usually out to steal something. The AD&D Player’s Handbook cover by Dave Trampier perfectly captures what you do in D&D: delve dungeons, read maps, kill monsters, and take their stuff.

So in settings like Greyhawk and the Forgotten Realms, at least, “adventurer” is an in-universe job. Some people are adventurers. It’s a lucrative, but very dangerous profession. Some people, like Daran Edermath, do it for a while and then retire to a small town to live out their days in peace. Some, like Gygax’s own PC Mordenkainen or any sufficiently high-level OD&D “Fighting Man” reach a point of history-bending influence where adventuring isn’t the best way to make money anymore. Others… Well look, all the skeletons, chewed bones, and slowly dissolving equipment in a gelatinous cube have to have come from someone, right?

Modern editions have moved away from the idea that the rules should en masse result in a collective world that reflects the fiction. Instead, in 5e, at level 1, you’re already, mechanically, special. Mechanically, most people in the world are Commoners. Not too far from the “human” average of 10 in each stat. But you are going to be an adventurer—in addition to whatever backstory reasons you might have—because you can. Because you have found yourself a few standard deviations away from the norm, and that gives you the option. To borrow from Saterade: not every 6’7″ person plays basketball professionally, but you’ll be hard pressed to find a lot of people my height in the NBA.

It isn’t that your party isn’t the only adventuring group out there—unless you’re in a homebrew setting where they are, of course. Or the only powerful people in the world. It’s hard to imagine a D&D setting without some seemingly aloof high-level magic users, or red-haired former-adventurer tavern owners. If you’re in the Forgotten Realms, the Silverhand sisters, Drizzt, Elminster, Jarlaxle, and so many others have been adventuring since before you were born.

(The concept of “power” that exists in-universe in D&D, and other settings like Dragon Ball, is fascinating and worthy of its own rambly post.)

Our smith might have a 13 or 14 Strength score, and maybe even proficiency with a longsword—it’s a dangerous world after all. But that doesn’t mean they are, or perceive themselves to be, cut out for professional adventuring.

So what are the options our smith has when their business is burned by dragon’s breath? Fighting dragons is risky, even for established, professional adventurers: our smith might not even consider them fightable by normal people. It’d be like trying to get revenge on a hurricane—a dragon is basically a force of nature to them. Or maybe the risk outweighs any possible benefit—they’re likely to die on this quest, and for what? Especially if they have surviving family.

Or maybe, they do go. There are lots of adventurers, after all, maybe this dragon attack was their tragic backstory. Revenge or treasure, and their self-confidence, is enough to push them towards the danger.

Sure, they might die, but they might win! Maybe while your party, the local adventurers who just saved the town, went off and dealt with the necromancer, the smith got a group or posse together and they took the fight to the dragon. And you missed it.

One of the great and unique things about tabletop RPGs is that the world is not only persistent, but it moves along off-screen. If you follow plot hook A, you won’t be there to stop plot hook B. As Noam pointed out, it’s always worth understanding what would might happen if the PCs don’t show up. The Countdown from Monster of the Week pushes you to think what will happen off-screen. The Alexandrian calls it having goal-oriented opponents. There’s not only a sense of urgency but also of exigency—credit again to Colville for making me think about this, it’s worth its own post, too.

But even if the NPC blacksmith goes and fights the dragon and wins, we’re not going to put it on screen. Because we’re not telling the story of the blacksmith—that’s a book, not an RPG.

D&D is rooted in sword & sorcery, but I think most modern players, at least most newer players, at least most players I know, have at least one foot in epic or heroic fantasy. Aragorn and Frodo are more common archetypes than Conan or Elric. Or even Bilbo—the original halfling Thief who just wanted an adventure. And the design trend of TTRPGs since the 90s is toward this type of narrative-driven “storytelling”, while other games like Gloomhaven have filled the pure “delve dungeons, kill monsters” niche.

5e also grounds progression in heroism. Levels 1–4 are Local Heroes, where “the fate of a village” might hang on your campaign. (Many 1e adventures like Against the Cult of the Reptile God start in the same place.) But if you play a campaign long enough, you get to levels 17–20: Masters of the World. You don’t have to save the world, but if you are still looking for a gameplay challenge or satisfying narrative, you may well do so.

So why, of all of these adventurers out there, is your group the one to stand up to the BBEG? Because this is your story.

Ultimately, the “camera” is going to focus on the PCs. Anything that happens off-screen—whether the blacksmith stays home, kills the dragon, or dies trying—is background detail in the world because this world only exists to tell the story of the PCs. If you put a PC into the Total Perspective Vortex, they’d come out happily munching on a piece of cake.

If we were telling the story of “how the blacksmith slew the dragon,” one of the PCs would be the blacksmith. If we wanted to tell the story of Allura and Kima imprisoning Thordak, the PCs wouldn’t be Keyleth and Pike. Gandalf must mark Bilbo’s door, because whoever’s door he marks is Bilbo. If he’d shown up at Rosamund Took’s, then Rosamund would be Bilbo as we know him.

In other media, using the perspective of audience proxy characters—C3PO and R2 in Star Wars, their progenitors Tahei and Matashichi in The Hidden Fortress, to some extent Nick Carraway in Gatsby—can be an effective way to frame a story. But in a TTRPG, the PCs are the main characters, whatever the PCs do. That isn’t to say other, bigger activity doesn’t happen. In a war setting, the PCs probably aren’t the most influential characters—but the war is the backdrop of their story.

Sometimes an aside to look at someone else can be great. The Zeppo is one of my favorite Buffy episodes. There’s an arc on the Critshow where the main hunters are all captured, so the players step into the roles of the previous generation, called out of retirement to help. Mechanically, it can also be a good way to change things up, take a bit of a breather.

But if I put Chekhov’s Mage into a low-level campaign, I’m not going to say “oh yeah, Alustriel and Elminster handled that.” It’s one thing for the town blacksmith, bard, and bowman to fight the local dragon, but if there’s a big, narrative threat, and the PCs don’t deal with it, then the BBEG pretty much gets to succeed at whatever they’re doing. And if there’s a TPK and we roll up new characters, then the last group—and possibly that BBEG’s success—becomes part of the background of the new one.

Excellent article. It’s also a great reminder to post up my backstory for my friends Kineticist whose entire family is still alive and happy and running a successful circus.

People just keep sending him to more and more dangerous places because he has a terminally boring demeanour.

30 plus years of roleplaying and finally someone has living parents that aren’t evil.

LikeLike

I definitely fell into the dead family trap/trope with my first PC but love to see a happy family! Plus as a DM, the more connections a PC has, the more people available to put in peril!

LikeLike

The Mags post for my Midkemia Wizard school game has all his family ‘whereabouts unknown’ for three different reasons. It’s nice for the GM to play with AND gives him a reason for his horrendous burning rage. ( red magic)

LikeLike